Willcocks (1919) understood that the Shuruppak flood had been recast as Noah's flood and that the flat desert plain about Shuruppak may have in antiquity been confusingly called a "mountain" noting such language was employed by modern Arabs, as regards the word Jebel, Gebel, Djebel, meaning mountain, hill, plain and desert (Willcocks apparently was not aware that the Akkadian/Babylonian word kur could mean land, region, and mountain)

"Jebel or gebel in literary Arabic is a hill or mountain, but in the spoken language of Egypt and Arabia it is "the desert." In Egypt today the reef is the irrigated plain, and everything else is the jebel or gebel, the desert, be it a plain, a hill, or a mountain...mentioning these facts to Colonel Ramsay...and to Mr. Van Ess...on a steamer in the Nejef marshes, we agreed to test the matter on the Euphrates. Approaching Shinafia, we saw the low degraded desert on the horizon, and I asked the boatmen what that was; they immediately replied "The jebel." It was no more like a hill than Ludgate is like a mountain."

(p. 20. William Willcocks. From the Garden of Eden to the crossing of the Jordan. London. E. & F. N. Spon, Ltd. 1919)

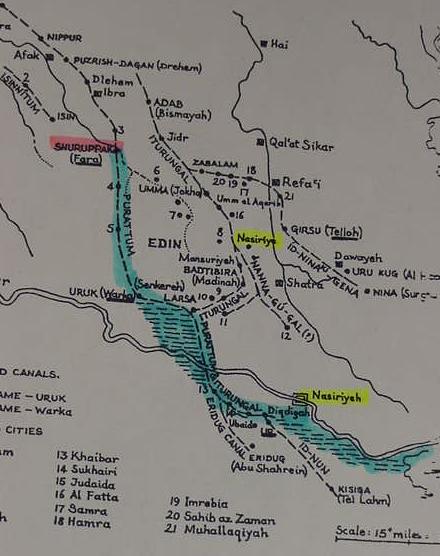

The Flood hero, Atra-Khasis resides at Shuruppak described as being on the Euphrates river. He is to construct a boat, and apparently launch it onto the river, it is really quite small as he equips it with "punting poles" for navigation in some of the various flood recensions. So as to not let the people know a flood is emminent, the flood hero to told to mislead the people telling them he has angered the god Enlil and is constructing the boat to live with Enki at the apsu. The apsu is a mythical underground watery dwelling for Enki at Eridu. So, apparently Atra-Khasis will, via the Euphrates river, glide downstream (east-south-east) from Shuruppak to Eridu. The Atra-Khasis epic mentions in the course of the flood the dead bodies of people, likened to dragonflies, littering the river and its bank (the bodies having beached themselves on the bank like a wayward raft), clearly placing the flood and its dead bodies in the vicinity of the Euphrates river. I have proposed that kur Nisir means "land of Nisir" and that this area is to be identified with modern-day an-Nasiriyeh some 22 kilometers (14 miles) east-north-east of Eridu. Like Eridu, an-Nasiriyeh lies east-south-east and downstream from Shuruppak.

Surprisingly, so convinced was Willcocks in 1919 that the Gilgamesh Flood at Shuruppak was of a mountain-jebel-desert, because the area about Shuruppak is a flat desert plain that he even substituted the word "mountain" for desert, that is to say for him "mount Nisir" where the ark beached itself became "the _desert_ of Nisir":

"I have changed the word "hill" or "mountain," which would be quite out of place in Babylonia, into "desert."

(p. 33. Willcocks. 1919)

"To the desert of Nisir the ark made its way;

The desert of Nisir would not let it pass."

(p. 32. Willcocks. 1919)

I understand that the "high ground" about modern day an Nasariyah on the Euphrates is "mount" or Kur Nisir.

Allusions in the Epic of Atra-Khasis to the flood as being a flooding Euphrates river caused by a rain storm (I have not reproduced the scholarly ellipses and brackets for restored portions of the texts):

"Let Errakal tear up the mooring poles,

Let Ninurta go and make the dykes overflow...

They have filled the river like dragon flies!

Like a raft they have put in to the edge,

Like a raft...they have put in to the bank!

...For seven days and seven nights

Came the deluge, the storm, the flood..."

(pp. 87, 97. W. G. Lambert & A. R. Millard. Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood. Winona Lake, Indiana. 1999. Eisenbrauns)

As noted above by Dalley, the Sumerian account says nothing about the Shuruppak boat grounding on a mountain, it could just as well have grounded on land exposed by receding floodwaters somewhere in the Lower Mesopotamian floodplain. The Akkadian/Babylonian account has the craft beaching on a kur nisir which can be rendered either "land of nisir" or "mountain of nisir." I have given above, my reasons for understanding why a "land of Nisir" (kur Nisir) was morphed into a "mountian of Nisir." This is not the end of the matter: A later Neo-Assyrian recension has the boat grounding on a "mount Nimush" instead of mount Nisir while the Hebrew Bible has the boat beached somewhere in the "mountains of Ararat," understood to be the Hebrew rendering of Neo-Assyrian Urartu, a mountainous kingdom near modern Lake Van. Note: the Bible does _not_ say the boat is on a mountain called Ararat, it is in the mountains of Ararat. If my suppositions are correct, that kur Nisir is to be identified with modern-day an-Nasiriyah ENE of Ur and Eridu, then it stands to reason that the boat will most likely never be found. It would have been later scrapped for fire-wood or building-material after its usefulness as a river craft had come to its end. In part one of this article I have provided the reader with a photograph of a boat appearing on a stele at Shuruppak dated circa 2600 B.C. and identified this craft as most likely what Atra-Khasis' boat originally looked like before later generations morphed this four-man canoe into a gigantic craft able to hold all the species of the world. Please click here and scroll down for pictures of the canoe that became Noah's Ark.

Professor Skinner (1910) on the Mesopotamian Flood account being a somewhat tongue-in-cheek "farcial and satirical" work in its making fun of the gods:

"The gods of the Babylonian version are vindictive, capricious, divided in counsel, false to each other and to men; the writer speaks of them with little reverence, and appears to indulge in flashes of Homeric satire at their expense."

(p. 178. "The Deluge Tradition." John Skinner. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Genesis. Edinburgh, Scotland. T. & T. Clark. 1910, revised edition 1930, reprinted 1994)

Professor Cohn (Professor Emeritus at the University of Sussex, Sussex, England) on the gods who brought about the Flood being shown in a satirical and farcial manner (emphasis mine):

"The author of the Atrahasis Epic clearly thinks well of mankind, poorly of almost all the gods. This is not a story about sin and its consequences. Although Mesopotamians were familiar with the notion of sin, it is not sin that precipitates the Flood. The offence of human beings is simply that they multiply and, as a result, make too much noise for the gods' comfort. That such a slight and unwitting offence evokes such a lethal response is due to the shortcomings of the gods: they are tyrants- and stupid tyrants at that. If the gods were less stupid, if they had the slightest capacity for forethought and rational planning, they would have borne in mind their total dependence on mankind. For had not human beings been created precisely because the gods could not provide for themselves?

The chief god Enlil cuts a particularly sorry figure. He is supposed to be a mighty leader, yet when the lesser gods beseige his house he has to call on the assembly of the gods and then urge Enki to deal with the situation. And when human beings in their turn produce new problems, Enlil's reaction is at first ineffective, and so imprudent that the very survival of the gods is called into question. But the criticism directed against Enlil involves almost all the gods. For -as the mother-goddess points out- the whole assembly of the gods consented to the Flood. The picture that the poet paints of the gods when faced with the consequences -how they suffer thirst and hunger pangs, and how later they swarm about Atrahasis' offerings- makes them look both contemptible and ridiculous. Only Enki is exempt: he alone foresees problems and solves them when they arise..."

(pp. 6-7. "Mesopotamian Origins." Norman Cohn. Noah's Flood, the Genesis Story in Western Thought. New Haven & London. Yale University Press. 1996)

Kramer mentions a Hittite myth which has Ea (Enki) advising Hittite gods that if man is annhilated the gods will have to work their fields for their own sustenance, plowing and milling grain for bread, the gods will lose their rest from work made possible by man who was created to toil in their place and provide them their sustenance (emphasis mine):

"Ea, king of wisdom, spoke among the gods...

he began to speak: "Why annihilate the humans?

Do they not give the gods offerings and burn cedar wood for you?

If the humans were destroyed for her, the gods would

no longer REST FROM WORK,

and no one would contribute bread and drink to you any longer.

It will turn out that the storm-god,

mighty king of Kummiya, the plow

will take up himself! And it will turn out that

Ishtar and Hebat

will turn the mill themselves!"

(p. 152. "The Uses of Mankind." Samuel Noah Kramer & John Maier. Myths of Enki, The Crafty God. New York & Oxford. Oxford University Press. 1989)

The above Hittite myth suggests that Ea (Sumerian Enki of Eridu in Sumer, Lower Mesopotamia, modern Iraq) realized that the destruction of mankind by a Flood was an act of rash stupidity on Enlil's part, for the gods would have to toil again for their own food in edin's gardens if man was annihilated. In other words Ea warned Atra-Khasis (Ziusudra, Utnapishtim) of the Flood out of self-interest, not because he loved or cared about mankind; he didn't want to have to toil for his food in edin's gardens because of mankind's demise. The Hebrews, denying the Mesopotamian notion for _why_ a god warned a man to build a boat to save the seed of man and animal-kind, portray their God as giving this warning to a man as an act of righteousness: Noah is righteous, he deserves to have his life spared, whereas the rest of mankind is unrighteous and deserves annihilation. So, in the Mesopotamian understanding, Ea acted out of callous self-interest, he knew that if all of mankind was annihilated he and the other gods of edin would have to bear again the grievous toil in edin's gardens to provide food for themselves. They and he would lose forever their eternal Sabbath Rest from earthly toil with man's annihilation. The Mesopotamians blamed unrighteous gods for the Flood, not innocent, cruelly god-exploited man. A man (Atra-Khasis) was warned to build a boat by a god not because he was more righteous than his fellow man but because the god of wisdom, Ea, forsaw the dire consequences for himself and his fellow gods if Enlil's rash act was succesful in the complete annihilation of man.

The Hebrews have then, _inverted_ and transformed the Mesopotamian Flood myth: God (Yahweh-Elohim) is righteous and mankind is evil and deserves annihilation.

In the Mesopotamian account of the Flood the gods regret and are tearful over their decision to annihilate mankind (Emphasis Mine):

"Ishtar cried out like a woman in travail,

The sweet-voiced mistress of the [gods] moans aloud:

'The olden days are alas turned to clay,

Because I bespoke evil in the Assembly of the gods,

How could I bespeak evil in the Assembly

of the gods,

Ordering battle for the destruction of my people,

when it is myself who give birth to my people!

Like the spawn of the fishes they fill the sea!'

The Anunnaki GODS WEEP WITH HER,

THE GODS, ALL HUMBLED, SIT AND WEEP..."

(p. 69. "The Epic of Gilgamesh." James B. Pritchard. Editor. The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton University Press. 1958. Paperback. Library of Congress Card Catalogue number: LC Card 58-10052)

Tears run down the face of the Mesopotamian "Noah," he realizing mankind has been destroyed:

"The sea grew quiet, the tempest was still, the flood ceased.

I looked at the weather; stillness had set in,

And all of mankind had returned to clay...

Bowing low, I SAT AND WEPT,

TEARS RUNNING DOWN ON MY FACE."

(p. 69. "The Epic of Gilgamesh." James B. Pritchard. Editor. The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton University Press. 1958. Paperback. Library of Congress Card Catalogue number: LC Card 58-10052)

After the Flood, the Mesopotamian "Noah" erects an altar and makes thank-offerings for his deliverance. The Akkadian goddess Ishtar (Sumerian: Inanna) arrives and announces that Enlil (Akkadian: Ellil) should not be allowed to come and partake of this offering for he _irrationally_ instigated the flood:

"Let the gods come to the offering;

(But) let not Enlil come to the offering,

For he, _unreasoning_, brought on the deluge

And my people consigned to destruction.' "

(p. 70. "The Epic of Gilgamesh." James B. Pritchard. Editor. The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton University Press. 1958. Paperback. Library of Congress Card Catalogue number: L.C. Card 58-10052)

Ishtar (Sumerian: Inanna) is not the only deity who castigates Enlil (Akkadian Ellil) for _irrationally_ or "_unjustifiably_" destroying humankind with the Flood, the god Ea (Sumerian Enki) also accuses him of killing innocents as well as sinners and pleads with him to never send another Flood but to instead use less drastic means to curb mankind's population growth.

Belet-ili is a title of Ishtar's, she and Ea both accuse Enlil of overreacting in sending a flood to destroy _all_ of mankind, less drastic curbs to control noisey man should be resorted to and Ea pleads for _leniency_ for trangressors, punish, do not slay the sinner:

"...Belet-ili arrived...

"Enlil should not come to the incense offering,

For he irrationally, brought on the flood,

And marked my people for destruction!"...

Ea made ready to speak,

Said to the valiant Enlil:

"You, O valiant one, are the wisest of the gods,

How could you, irrationally, have brought on the flood?

Punish the transgressor for his transgression,

But be lenient, lest he be cut off,

Bear with him lest he [...].

Instead of your bringing on a flood,

Let the lion rise up to diminish the human race!"

(p. 90. Benjamin R. Foster. The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York & London. W.W. Norton & Company. 2001)

Sandars' paraphrase of the above verses also suggests that Ea is pleading for leniency or mercy for sinners: punish do not slay them:

"Then Ea opened his mouth and spoke to warrior Enlil, "Wisest of gods, hero Enlil, how could you so senselessly bring down the flood?

"Lay upon the sinner his sin,

Lay upon the transgressor his transgression,

Punish him a little when he breaks loose,

Do not drive him too hard or he perishes;

Would that a lion had ravaged mankind

Rather than the flood..."

(p. 109. "The Story of the Flood." Nancy K. Sandars. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Baltimore, Maryland. Penguin Books. 1969)

Yahweh-Elohim shows no remorse over destroying man with a flood unlike the Mesopotamian gods who weep with Inanna/Ishtar (Belet-ili) over their rash ill-advised decision. Genesis' Noah, unlike the Mesopotamian Noah (variously called Ziusudra, Atrahasis, Utnapishtim) shows no remorse over humankind's destruction, no tears flood down Noah's face. The Mesopotamian flood myth portrays the gods regretting their decision in assenting to Enlil's demand that humankind be destroyed for violating his rest/sleep with their noise. Yahweh does _not_ regret his decision to destroy mankind, his regret is that he ever made mankind _and_ animalkind as well:

Genesis 6:7, 11-13 RSV

"So the Lord said, "I will blot out man whom I created from the face of the ground, MAN AND BEAST and creeping things and birds of the air, FOR I AM SORRY THAT I HAVE MADE THEM...And God saw the earth, and behold, it was corrupt; FOR _ALL_ FLESH HAD CORRUPTED THEIR WAY upon the earth. And God said to Noah, "I have determined to make AN END OF _ALL_ FLESH; for the earth is filled WITH VIOLENCE THROUGH THEM; behold, I will destroy them with the earth."

We are _not_ told in Genesis that animal-kind has eaten of the "forbidden fruit," _only_ mankind (Adam and Eve), so why is God portrayed as claiming that "ALL FLESH," including animalkind, has "corrupted their way" and filled the earth with bloodshed and violence?

I suspect that this notion of animalkind filling the earth with violence is ancient man's observation that the living must feed off the living. A life-form must give up its life to sustain another life. In order to sustain life carnivores must _shed blood_, violently killing their prey to feed off them. Perhaps this is what is being alluded to as Genesis portrays all animals in the beginning eating every green plant for food instead of each other:

Genesis 1:29-31 TANAKH

"God said, "See, I give you every seed-bearing plant that is upon all the earth, and every tree that has seed-bearing fruit; they shall be yours for food. And to all the animals on land, to all the birds of the sky, and to everything that creeps on earth, in which there is the breath of life, [I give] all the green plants for food." And it was so. And God saw all that he had made, and found it very good."

(TANAKH, The Holy Scriptures. Philadelphia & New York. The Jewish Publication Society. 1988. Year of Creation: 5748)

Evolutionary Biology understands that carnivores did _not_ have a "change of spirit" and give up eating grass to eat flesh instead. They possess canine teeth to rip off flesh and claws to grip their prey. Had _all_ animals (lions, spiders, lizards, ants, scorpions, snakes, eagles, vultures, falcons) in the beginning been "herbivores" as portrayed by Genesis, the earth's fossil evidence would indicate this (no canine teeth, no claws). Genesis' notion that all the animals in Eden were herbivores including lions and leopards is nonsense and not supported by the fossil evidence. So, where then is Genesis getting this notion that there is "no fear for man in Eden" because all its creatures are herbivores? This notion is apparently a recasting of similar motifs appearing in various Mesopotamian myths regarding primeval naked man who is a vegetarian who has no fear of creatures in the edin he roams because his companions (naked Enkidu's cattle and gazelles in the edin) are herbivores. Please click here and scroll down to "the end" of my article (identifying the location of Eden on a map) for all the details.

The Hebrews in recasting the Mesopotamian flood myth _are challenging_ the Mesopotamian reasons for WHY man was destroyed, and they are _challenging_ the notion that this act of destruction was _irrational_ and _unwarranted_ on Enlil's part as noted by Inanna/Ishtar's and Enki/Ea's accusations brought against Enlil/Ellil. In otherwords the Mesopotamian account of the Flood portrays man and animal as _innocent victims_ of irrational, vindictive gods, whereas the Hebrews have recast all this as evil, violent, blood-shedding man and animalkind deserving of punishment by an outraged God. The Hebrews have reversed and inverted the reasons for the Flood, they deny "unjust gods" as being responsible for the Flood, it is a "just God" who brought this event about.

Who's is the "more compassionate" God, the Hebrews' Yahweh-Elohim who sheds no tears, and who regrets the making of humankind or the Mesopotamian gods who shed tears of repentance over their rash action?

Who's Noah is "more compassionate" the Hebrew Noah who expresses no regret over man's demise, shedding not a single tear, or the Mesopotamian Noah who slumps down in his boat tears flooding his face over his fellow-man's demise?

Yahweh declares he regrets not only the making of mankind but also animal-kind as well. The Mesopotamian flood myth makes no mention of the gods hating animalkind and deliberately seeking its destruction. It is because man's noise disturb's Enlil's rest/sleep that he _irrationally_ subjects all of the creation, including innocent beasts, to destruction.

For my part, it is the 2nd-1st millennium B.C. Mesopotamian versions of the mythical Shuruppak Flood of circa 2900 B.C. that portrays the "more compassionate" and "contrite" gods.

Christians understand that the God who brought about Noah's Flood and regretted that he had created both humankind and animalkind was Jesus Christ in his role as "The Word" (Greek: Logos):

John 1:1,14 RSV

"In the beginning wasTHE WORD, and THE Word was with God, and THE WORD was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made...And THE WORD became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father."

Stiebing remarks on the biblical recasting of the Mesopotamian Flood myth:

"Thus, looking at the perspective from which the Biblical writers viewed their Flood stories, and examining the context into which they placed these stories, one cannot help but feel that the Flood tradition has undergone a qualitative change since being removed from Mesopotamia. That the Old Testament contains mythological elements and that it preserved some legendary stories which originated in Mesopotamia or in other cultures of the ancient Near East is to be expected. What is surprising is the degree to which these myths and legends have been transformed by the ancient Israelite conviction..."

(p. 28. William H. Stiebing, Jr. "A Futile Quest, The Search for Noah's Ark." pp. 15-29. Molly Dewsnap Meinhardt. Editor. Mysteries of the Bible, From the Location of Eden to the Shroud of Turin. Washington, D.C. Biblical Archaeology Society. 2004)

Bright on Tell Fara's Flood layer:

"The evidence from Fara. During excavations at this site in 1931 a sterile, alluvial layer some two feet thick was found between the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic layers- thus indicating an inundation at the site which was earlier than the one at Kish and yet much later than the one at Ur (see Schmidt, Museum Journal, XXII, 193 ff.)."

(p. 35. John Bright. "Has Archaeology Found Evidence of the Flood?" pp. 32-40. G. Ernest Wright & David Noel Freedman. Editors. The Biblical Archaeologist Reader. Chicago. Quadrangle Books, Inc. 1961. [The articles contained within were reprinted from The Biblical Archaeologist magazine])

Bright on how the Hebrews obtained knowledge of the Mesopotamian Flood account:

"It is quite clear that the Hebrew story is derived directly or indirectly from the ancient Sumerian...How then did the Hebrews in Palestine get their Flood tradition? Two alternates present themselves. (1) They learned it from the Canaanites in Palestine, who, in turn, learned it from Mesopotamia...(2)...the ancestors of the Hebrews brought the story with them when they migrated from Mesopotamia in the Patriarchal Age." (pp. 39-40. Bright)

Bright on how the Hebrews have given the Flood story a new twist, instead of the Flood being sent to end man's noise which disturbs the gods, an outraged God destroys man for filling the world with much bloodshed and violence:

"The most significant thing about it is not its historical antecedents or its archaeological basis. Its actual significance lies in its religious outlook. In Genesis the Flood is not caused by mere chance or the whim of capricious brawling gods. It is brought about by the One God in whose hands even natural catastrophe ia a means of moral judgement...To the Israelite writers the telling of the story has become an opportunity of demonstrating and illustrating the righteousness of God." (p. 40. Bright)

I have no complaint with Bright's analysis. He rightly notes that man is to blame for the Flood in the book of Genesis. Man in the Bible is cast as a depraved, violent shedder of human blood and he deserves the punishment he gets.

All this is very different from the Mesopotamian account, a 180 degree reversal or inversion.

In the Mesopotamian myths man was created to be a toiling agricultural slave of the gods. He is created because the junior gods, the Igigi rebelled against the senior gods, the Anunnaki at Nippur in Sumer (cf. the Atra-Khasis Epic for all the details). The Igigi complained for 40 years night and day of their grievous toil excavating irrigation ditches to provide water for Enlil's city-garden. When they rebel, Enlil calls for help from his brother god Enki of Eridu. Enki suggests replacing the Igigi with man and Enlil agrees. When man is created we are told that the clamor or noise of the Igigi is transferred to man.

That is to say man's clamor or noise is apparently that of the Igigi, a protest over the grievous work in the gods' city-gardens. Enlil's response to man's clamor is very different to his earlier response to the Igigi's clamor, instead of allowing man to enjoy an eternal rest from toil like the Igigi he _denies_ man this boon and sends a Flood to annihilate mankind. That is to say man's noise that disturbed the gods' rest, causing them to send a Flood was over the grievous toil they endured in the gods' city-gardens located in the midst of eden/edin (eden/edin is the Sumerian word for uncultivated steppeland surrounding the gods' city-gardens of Lower Mesopotamia, present day Iraq).

So, in the Mesopotamian myths innocent, oppressed mankind was annihilated by _unrighteous_ gods because of his noise, his protesting the grievous labor and his desiring a rest from toil as granted to the Igigi.

The gods are then, being faulted by the Mesopotamian storyteller, not mankind!

It is the gods who acted _unrighteously_ in sending a Flood to destroy an oppressed noisey mankind.

The Hebrews have recast all of this. God is portrayed as being _righteous_ in sending the Flood and it is mankind who is _unrighteous_ in that he has shed much human blood and is therefore worthy of annihilation.

Some readers may have an interest in the Scientific evidence which suggests Noah's Flood is a myth. The below articles also refute the bible-believing "Creationists" who argue the earth was created 6000 years ago as portrayed in Genesis, the Flood occuring in the 3rd millennium B.C. and explain why Creationist refutations of the Scientific evidence are wrong-headed and employ flawed unscientific methodologies (Please click on the below underlined blue urls to access the articles):

Edward T. Babinski. Creationist "Flood Geology" Vs Common Sense.

Edward T. Babinski. Why I Believe the Earth Is Old.

Paul H. Seely. The GISP2 Ice Core, Ultimate Proof that Noah's Flood was not Global.

(Ice corings from Iceland's glaciers reveal layers of ice as old as 110,000 years before the present era)

Six-Day Creationism and its Young Earth Creationist Advocates (A critique of their arguments for Noah's Flood being a real event)

Another "problem" with Noah's Flood being dated by the Bible's internal chronology to the 3rd millennium B.C. and engulfing the world is that the Egyptian Pharaonic Civilization "predates" this Flood. Clayton gives the following dates for Egyptian Dynasties and their Pharaohs (Peter A. Clayton. Chronicle of the Pharaohs, The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London. Thames & Hudson. 1994):

Dynasty 0

3150-3050 B.C.

Dynasty 1

3050-2890 B.C.

Dynasty 2

2890-2686 B.C.

Dynasty 3

2686-2613 B.C.

Dynasty 4

2613-2498 B.C.

Dynasty 5

2498-2345 B.C.

Dynasty 6

2345-2181 B.C.

If there was a "universal" globe-encompassing Flood in the third millennium B.C. there is no evidence of it in Egypt, Noah's Flood being 2958 B.C. as calculated by the Roman Catholic scholar Euseibus or 2348 B.C. as calculated by the Protestant scholar Arch-bishop James Ussher.

That is to say archaeologists have unearthed the tombs of the above Pharaohs for the above six Dynasties (3150-2181 B.C.) and found _no_ flood layer of silt "above their tombs" deposited by Noah's alleged Universal Flood. Nor do the records or annals of Egypt make any mention of a universal world-encompassing Flood. The absence of the mention of such a flood in Egyptian records and annals combined with the archaeological evidence from the Pharaoh's tombs created _before_ the 2958/2348 B.C. Flood occurred (excavations showing no Flood silts being deposited over the tombs) reveal that Noah's Flood is a myth.

Bibliography:

Lloyd R. Bailey. Noah, the Person and the Story in History and Tradition. Columbia, South Carolina. University of South Carolina Press. 1989. ISBN 0-87249-637-6. paperback.

Lloyd R. Bailey. Genesis, Creation and Creationism. New York & Mahwah, New Jersey. Paulist Press. 1993.

Jeremy Black, Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson & Gabor Zolyomi. The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. 2004, 2006.

Robert M. Best. Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic. Fort Myers, Florida. Enlil Press. 1999.

Piotr Bienkowski & Alan Millard. p. 98. "Ea." Dictionary of the Ancient Near East. Philadelphia. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2000.

John Bright. "Has Archaeology Found Any Evidence of the Flood?" pp. 32-40. G. Ernest Wright & David Noel Freedman, editors. The Biblical Archaeologist Reader. Chicago. Quadrangle Books. 1961.

Umberto Cassuto. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis, From Adam to Noah. Jerusalem. Magness Press. The Hebrew University. 1944 [in Hebrew]. 1989 English edition.

Peter A. Clayton. Chronicle of the Pharaohs, The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London. Thames & Hudson. 1994.

Eric H. Cline. From Eden to Exile, Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. Washington, D.C. National Geographic. 2007.

Norman Cohn. Noah's Flood, The Genesis Story in Western Thought. New Haven & London. Yale University Press. 1996.

Harriet Crawford & Michael Rice, editors. Traces of Paradise, The Archaeology of Bahrain, 2500 B.C.-300 A.D. London. 2000. Paperback catalogue to accompany an exhibition of objects on loan from the Bahrain Museum.

Stephanie Dalley. p. 110. "Gilgamesh XI. Myths from Mesopotamia, Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, And Others. Oxford & New York. Oxford University Press. 1989.

Brian Fagan. "Searching for Eden." pp.147-164. Time Detectives, How Scientists Use Modern Technology to Unravel the Secrets of the Past. New York. Touchstone Books [Simon & Schuster]. 1995, 1996.

Jack Finegan. Handbook of Biblical Chronology, Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible. Revised Edition. Peabody, Massachusetts. Hendrickson Publishers. 1964, 1998.

Benjamin R. Foster. The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York & London. W. W. Norton & Co. 2001. [A Norton Critical Edition].

Henri Frankfort. The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient. New Haven & London. Yale University Press. 1954. 4th edition 1970. Reprint 1996.

Andrew George. The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. London. The Penguin Press. 1999, 2000, 2003.

John Gray. Near Eastern Mythology. London. Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. 1969.

Alexander Heidel. The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 1946, 1949. reprint 1993.

Barthel Hrouda. Editor. Der Alte Orient, Geschichte und Kultur des alten Vorderasians. C. Bertelsmann Verlag. Munchen, Deutschland. 1991.

Morris Jastrow, Jr. Handbooks on the History of Religions: The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Boston. Ginn & Company, Publishers. 1898.

Samuel Noah Kramer & John Maier. Myths of Enki, The Crafty God. New York. Oxford University Press. 1989.

Stephen Herbert Langdon. The Mythology of All Races: Semitic. Volume 5. Boston. Marshall Jones Company. Archaeological Institute of America. 1931.

W. G. Lambert & A. R. Millard. Atra-Hasis, The Babylonian Story of the Flood. With the Sumerian Flood Story [by M. Civil]. Winona Lake, Indiana. Eisenbrauns. 1999 reprint of 1969 Oxford University Press edition.

Gwendolyn Leick. Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. London. Penguin Books. 2001. paperback.

Charles Keith Maisels. p. 133. fig. 5.1 "Periodization of Mesopotamian History."

The Emergence of Civilization From hunting and gathering to agriculture, cities, and the state in the Near East. London & New York. Routledge. 1990, 1993.

Donald Maxwell. A Dweller in Mesopotamia. Being the Adventures of an Official Artist in the Garden of Eden. London & New York. John Lane & Company. 1921.

Patrick D. Miller, Jr. "Eridu, Dunnu, and Babel: A Study inComparative Mythology." pp. 143-168, in Richard S. Hess & David Toshio Tsumra, editors. "I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood." Ancient Near Eastern, Literary and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11. Winona Lake, Indiana. Eisenbrauns. 1994. Citing from a clay cuneiform text in the Assyrian king Asshurbanipal's library at Nineveh, CT 46.5.

James B. Pritchard. Editor. p. 66. "The Epic of Gilgamesh." The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton University Press. 1958.

Michael Roaf. Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East.New York. Facts On File, Inc. 1990.

H. W. F. Saggs. Babylonians [Peoples of the Past Series]. Berkeley & Los Angeles. University of California Press. [The British Musem. London. 2000].

William H. Shea. "The Flood: Just a local catastrophe?"

Eric Schmidt. "Excavations at Fara, 1931." University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal Vol. 22. 1931. pp. 193-217.

Charles E. Sellier & David W. Balsinger. The Incredible Discovery of Noah's Ark. New York. Dell Books. 1995.

John Skinner. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Genesis. Edinburgh, Scotland. T & T Clark. 1910, 1930 revised edition, reprinted 1994.

George Smith. The Chaldean Account of Genesis. London. 1875. Reprinted 1977, 1994 by Wizard Bookshelf. San Diego, California.

William H. Stiebing, Jr. "A Futile Quest, The Search for Noah's Ark." pp. 15-29. Molly Dewsnap Meinhardt. Editor. Mysteries of the Bible, From the Location of Eden to the Shroud of Turin. Washington, D.C. Biblical Archaeology Society. 2004.

William H. Steibing Jr. Uncovering the Past. New York & Oxford. Oxford University Press. 1994 [1993 Prometheus Books].

TANAKH . Philadelphia, PA. The Jewish Publication Society. 1985.

John H. Walton. Ancient Israelite Literature In Its Cultural Context. A Survey of Parallels Between Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Zondervan Publishing House.1989, 1990 Revised edition.

R. Norman Whybray. The Making of the Pentateuch, A Methodological Study. [Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Supplement Series 53] Sheffield, England. Sheffield Academic Press. 1987, reprint 1999.

Diane Wolkenstein & Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Her Stories and Hymns From Sumer. New York. Harper & Row. 1983.

Noah's Flood, the Archaeological and Geological evidence for its 3rd Millennium B.C. occurrence. (Including pictures of Noah's Ark) and it's Origins as an Amusing "Tongue-in-Cheek" Mesopotamian Farcial and Satirical Comedy!

PART TWO

Please click here for this website's most important article: Why the Bible Cannot be the Word of God.

For Christians visiting this website _my most important article_ is The Reception of God's Holy Spirit:

18 July 2005 (Revisions through 19 Feb. 2011)

On 29 November 2008 Google ranked this url Number One over 2,570 other urls when "mountain of Nisir" was keyed-in.

Professor George (2003) on Atra-Khasis (Atram-hasis) being an account of Man's origins up to the Flood and how the Flood motif from it reappears in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Holy Bible's book of Genesis:

"Another masterpiece of Babylonian literature known from late in the Babylonian period is the great poem of Atram-hasis, 'When the gods were man', which recounts the history of mankind from the Creation to the Flood. It was this text's account of the Flood that the poet of Gilgamesh used as a source for his own version of the Deluge myth. It also provided a striking model for the story of Noah's Flood in the Bible."

(p. xx. "Introduction." Andrew George. The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. London. The Penguin Press. 1999, 2000, 2003)

Cline, an Assistant Professor at Georgetown University, made an interesting observation about the search for Noah's Ark to the effect that if the biblical account is indebted to the Shuruppak Flood story found in the Epic of Gilgamesh why is no one searching for "mount" Nisir where the Shuruppak boat grounded?

"Why is no one searching for Mount Nisir, but numerous expeditions search on Mount Ararat, or the mountains of Ararat, looking for Noah's ark nearly every year?...These are questions for which I, and everyone else for that

matter, have yet to find answers."

(p. 37. "Noah's Ark." Eric H. Cline. From Eden to Exile, Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. 2007. National Geographic. Washington, D.C.)

According to Professor Jastrow (1898) nisir means "protection" or "salvation":

"After twelve double hours an island appeared,

The ship approached the mountain Nisir.

The name given the the first promontory to appear is significant. Nisir signifies 'protection' or 'salvation.' The houseboat clings to this spot. At this mountain, Nisir, the boat stuck fast."

(p. 503. Morris Jastrow, Jr. Handbooks on the History of Religions: The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Boston. Ginn & Company, Publishers. 1898)

I understand that the "historical kernel" behind Noah's Flood is the Mesopotamian flood story appearing in the Epics of Gilgamesh and Atra-khasis. The Flood hero resides at a city called Shurrupak when he is warned by his god to build a boat and put aboard it "the seed" of animals and man to preserve life. Shuruppak is identified with Tell Fara in

Mesopotamia, south of Babylon, and was excavated about 1931 by Eric Schmidt. Only _one_ flood layer was found at the site (dated circa 2900 B.C.), the sediment was determined to be from a flooding Euphrates rivers and its

adjacent irrigation canals. This layer of sediment was about 2 feet deep and did not cover all of Lower Mesopotamia, it was very local. So then, if Noah's Flood is based on the Shuruppak flood where is "mount" Nisir where the Shuruppak boat "grounded" itself?

In what follows I am attempting to apply "common-sense" in identifying this "mystery":

(1) As revealed by archaeology the Shuruppak flood was _not_ universal, covering the world's mountain tops, its local, near Tell Fara; (2) The flood was caused by the Euphrates river and when a river floods it eventually subsides, the

waters generally receding back into the river channel; (3) The Euphrates flows south-southeast from Tell Fara to the vicinity of Ur and Eridu; (4) "Assuming" the craft/boat eventually drifted _downstream_ from Tell Fara after the flood waters subsided, "mount" Nisir "might" be south-southeast of Fara and "near" the Euphrates; (5) The word _kur_ can be translated as "mountain," "underworld," "land," "country" or "region." (6) I am proposing that kur Nisir is _not_ the "mountain" of Nisir but the "land of Nisir" and I identify it with the land in the vicinity of the modern city of an-Nasiriyah, east-southeast of Tell Fara (Shuruppak) and near Ur and Eridu.

How did "kur" Nisir become "mount" Nisir instead of "land" of Nisir? Perhaps via:

(1) a misunderstanding or confusion or via

(2) a deliberate "playfulness" in casting a tall-tale for the "amusement" of an audience.

(1) Kur Nisir, if an-Nasiriyah, lies _downstream_ from Shuruppak, it is not unreasonable that a boat could reach kur Nisir/an-Nasiriyah from Fara, especially after the flood waters have receded back to the original channel. Someone at a much later point in time perhaps confused kur "land" into kur "mountain" and thus the flood was "morphed" into a worldwide event (if one kur-mountain is covered in water why not all the world's mountains?).

Alternately:

(2) Someone _deliberately and playfully_ transformed kur Nisir, "the land" of Nisir into a "mountain" of Nisir to make a rousing tall-tale for the amusement of his audience. He apparently thought little of the gods, characterizing them as "cowering dogs," in fear of the storm's destruction, so he could just as "playfully" or "tongue-in-cheek" transformed a kur "region" into a kur "mountain."

Best on kur Nisir meaning perhaps a sandbar in an estuary at the mouth of the Euphrates river near Eridu as being where the boat was grounded:

"line 140 a-na KUR ni- sir i-te-mid GIŠ eleppu

In country Nisir grounded wooden boat.

KUR ni- sir is usually translated "Mount Nisir" or "Mount Nimush" in imitation of the pseudo-biblical "Mount Ararat." But in Sumerian, KUR did not mean mountain, KUR meant hill or land or country. Nisir could be a placename, but it was not necessarily mountainous or even hilly. It was probable a local name of a land area or country. In my book I argue that the barge grounded on a sand bar or mound on a flat estuary at the mouth of the Euphrates River.

"line 141 KUR-ú KUR ni-sir GIŠ eleppu is-bat-ma a-na na-a-ši ul id-din

Mound [in] country Nisir wooden boat held-tight that its-movement not allowed.

The suffix -ú at the end of KUR-ú indicates that the first KUR should be read as shadú (hill or mountain) and not matu (country). This hill could be a small hill, even a mound. The text is consistent with the boat grounding on a sand bar or mound of silt or gravel in an estuary."

(Robert M. Best. Translation Errors in the Gilgamesh Flood Myth)

Best on ferreting out the real events behind the tall tale of a flood covering mountains:

"We should look beyond the mythmaker's mistakes and alterations and look for clues about the original stories in which the grounding place and the mountain were probably distinguished. In the context of a river barge grounding on a mudflat, the word shadu-u can mean a small mound that was normally submerged at the bottom of an estuary. My conjecture that shadu-ukur nisir should be read "mound, Nisir country" is more credible than identifying nisir with a mountain, because it would be impossible for the ocean to cover a mountain."

(pp. 197-198. Robert M. Best. Noah's Ark And the Ziusudra Epic. Fort Myers, Florida. Enlil Press. 1999)

Best noted that the flood-hero's announced destination upon his departure from Shuruppak by ship was the apsu where the god Ea (Sumerian Enki) lived. The apsu was at the city of Eridu, which in ancient texts was described as being at "the edge of the sea," hence the Euphrates which provided water for Eridu's crops would enter the sea at this location and thus the flood-hero's statement that he was after the flood placed in kur Dilmun, "the land of Dilmun/Telmun" at the "mouth of the rivers" suggests Dilmun is either the area of Eridu (and Ur?) or very nearby, (I have suggested Dilmun is possibly Tell al-Lahm in the marshlands).

Best understood that the flood-hero offered his post-flood sacrifice at Eridu near the mouth of the Euphrates river at its ziggurat or temple tower (cf. p. 198. Best. 1999). I note that modern-day an-Nasariyeh is near Eridu and Ur, which in ancient texts were described as lying "at the edge of the sea;" in other words in antiquity Ur, Eridu and Nasiriyeh may have lay near the mouth of the rivers (Euphrates and Tigris) which emptied into this "sea." Archaeologists have determined this "sea" is actually not a sea at all but an area of marshlands between Ur and Eridu and Basra. In these marshes lie lagoons and open areas of land with the remains of ancient settlements dating to the 2d millennium B.C.

Professor Clay (1923) mentions Professor King's theory that the Mesopotamian Flood hero's boat beached somewhere in Lower Babylonia, not on a mountain (in 1931 Shuruppak was excavated and found to have only one flood, circa 2900 B.C. which was a local flooding of the Euphrates river, King was right):

"Professor King also held. contrary to the position of many Babylonists that the story of the deluge is not a nature-myth, but a legend that had a basis of historical fact in Southern Babylonia. His idea is that the boat of legend was nothing more than the quffah, the familiar coracle of Baghdad, which is formed of wicker-work, and coated with bitumen. These craft, he wrote, "are often large enough to carry five or six horses and a dozen men." It is claimed that it was one of these that the original hero saved himself and his property; and landed, after the waters had abated, not in a mountain, but in Southern Babylonia."

(pp. 164-165. "The Deluge Story." Albert T. Clay. The Origin of Biblical Traditions, Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel. New Haven. Yale University Press. 1923)

Below, a picture of three copper ingots dated to circa 2000-1800 B.C. from an-Nasiriyah; we are told the Shuruppak flood hero did load aboard his craft his "valuables." Are these ingots some of Utnapishtim's "valuables"? Some scholars have suggested the Epic of Gilgamesh was composed anywhere from circa 2100-1800 B.C. and the above ingots "fall" in this general time period (cf. p. 78. figure 84-86. "Copper ingots, An-Nasiriyah, chance discovery, Early Dilmun, c. 2000-1800 B.C." Harriet Crawford & Michael Rice, editors. Traces of Paradise, The Archaeology of Bahrain, 2500 B.C.-300 A.D. London. 2000. Paperback catalogue to accompany an exhibition of objects on loan from the Bahrain Museum). The importance of these ingots isn't whether or not they are the Flood Hero's loot, their importance reveals that this region knew the "presence" of Sumerians circa 2000-1800 B.C. a timeframe when the Atra-Khasis Flood Hero account was believed to have been created by some scholars. So it is _possible_ that the modern Arabic an-Nasiriyah (a Turkish founded garrison town circa 1869) might preserve the Sumerian kur Nisir, "the land or region of Nisir."